We at the Road Racing Drivers Club are saddened by the passing of one of the most dynamic and iconic race-car drivers that have ever competed on race tracks around the world, Sir Stirling Moss. He was an honorary member of the RRDC since the 1960s and a good friend. Stirling was legendary in the sport, known for his ferocity on the race track, his many achievements in Formula 1 and sports-car endurance competition, and for his gentlemanly demeanor off the track. He will be missed. Our condolences go out to Lady Moss, whom we all know as Susie. – Bobby Rahal, RRDC President

To many of us of a certain age, Stirling Moss was a hero. When I was putting together the Playboy/Escort Showroom Stock Endurance Series in late 1984, my phone daily was ringing off the hook with queries from competitors, suppliers and manufacturers. The most memorable of those calls started out, “Stirling Moss here. Innes Ireland and I are interested in your new racing series.” Momentarily stunned, I quickly figured it was one of my erstwhile friends pulling my leg: “Okay, who is this really?” Louder than before: “It’s Stirling bloody Moss!” He and Innes ran a Brumos Porsche 944S for the season and were tireless promoters of the series. Stirling and Susie became friends, just as the two became friends with so many RRDC members. Our heartfelt condolences to Lady Susan and the Moss family. We will all miss him. – Bill King, RRDC webmaster.

The following is Sir Stirling Moss’s online obituary by Douglas Martin for the New York Times, April 12 [Front page image from Hulton Archive/Hulton Archive, via Getty Images; other images from various online sources]:

In the 1950s, small boys wanted to be Stirling Moss, and so did men.

Boys saw him as the swashbuckling racecar driver whom many considered the best in the world. Men saw this and more: Moss made more than $1 million a year, more than any other driver, and was invariably surrounded by the jet-set beauties who followed the international racing circuit.

Moss died quietly on Sunday at his home in London as one of his sport’s great legends. He was 90 and had been ill for some time.

“It was one lap too many,” his wife, Susie, told The Associated Press. “He just closed his eyes.”

Moss was a modern-day St. George, upholding the honor of England by often driving English cars, even though German and Italian ones were superior. Polls showed he was as popular as the queen.

Moss said courage and stupidity were pretty much synonymous, and may have proved it in a succession of spectacular accidents: seven times his wheels came off, eight times his brakes failed. He was a racer, he insisted, not a driver.

“To race a car through a turn at maximum possible speed when there is a great lawn to all sides is difficult,” he said in an interview with The New York Times Magazine in 1961, “but to race a car at maximum speed through a turn when there is a brick wall on one side and a precipice on the other — ah, that’s an achievement!”

He raced for 14 years, won 212 of his 529 races in events that included Grand Prix, sports cars and long-distance rallying, in 107 different types of car.

He set the world land speed record on the salt flats of Utah in 1957. He won more than 40 percent of the races he entered, including 16 Grand Prix. For four consecutive years, 1955-58, he finished second in the world Grand Prix championship. And in each of the next three years, he placed third.

“If Moss had put reason before passion,” said Enzo Ferrari, “he would have been world champion many times.”

He was called the best driver never to win the ultimate crown.

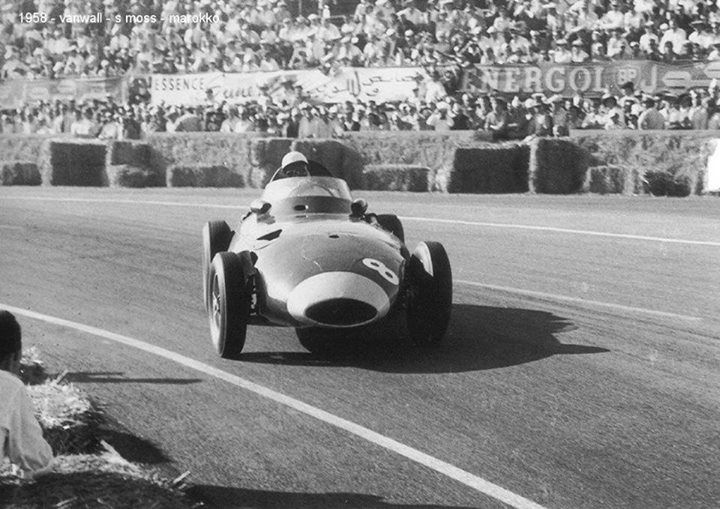

Moss’s propensity for signing with second-line British teams at the height of his powers was a World Championship hurdle he couldn’t quite clear. Here he hustles a Vanwall in 1958, one of his four title runner-up efforts. [Bernard Cahier image]

He came closest in 1958, but testified on behalf of another driver, Mike Hawthorn, who was accused of an infraction in the Portugal Grand Prix. Hawthorn, as a result, was not disqualified. When the season ended, Hawthorn had 42 points, which are given for factors like fastest lap as well as finishing position. Moss — though he had four Grand Prix wins to Hawthorn’s one — finished second with 41 points.

Polls of other drivers invariably named Moss No. 1, but it was his brash, puckish persona that captivated the public. He only reluctantly wore the required helmet, always white, saying he preferred a cloth cap.

In 1955, he won the Italian Mille Miglia, a 992-mile road race, in 10 hours, beating the field by 31 minutes. In 1958, he gambled to win the Argentine Grand Prix by not changing his tires the entire 80 laps, despite their having a design life of 40 laps. In 1961, driving a four-cylinder Lotus, he fought off three eight-cylinder Ferraris to win the Monaco Grand Prix.

Moss’s record-breaking drive in the 1955 Mille Miglia was immortalized by his co-driver Denis Jenkinson in “The Racing Driver”. [Sports Car Digest image]

In 1960, Moss won the United States Grand Prix five months after breaking both legs and his back at a Grand Prix race in Belgium.

A sinewy 5-foot-7, he favored short sleeves so he could get a suntan in his open cockpit. His seemingly casual slouch as he pushed howling machines to their limits was his signature. And his language elevated his sport almost to poetry.

Motion, he said, was tranquillity. Why, he wondered, do people walk, since God gave them feet that fit automotive pedals?

If people watch racing to witness the point where courage converges with catastrophe, Moss defined it.

In 1962 at the Goodwood Circuit racetrack in England’s West Sussex County, a plume of fire shot from his Lotus 18/21 car. The crowd gasped. As Moss tried to pass Graham Hill, his car veered and slammed into an eight-foot-high earthen bank.

It took more than a half-hour to free Moss from the wreckage. His left eye and cheekbone were shattered, his left arm broken and his left leg broken in two places.

An X-ray revealed a far worse injury, he didn’t even had the chance to call DWI traffic lawyers to help him recover. Garde Wilson Lawyers are traffic lawyers Melbourne with combined experience representing clients charged with driving offences, if you would like to be properly represented at Court then please call them. The right side of his brain was detached from his skull. He was in a coma for 38 days, and paralyzed on one side of his body for six months. He remembered nothing of the disaster. He considered hypnosis to recover the memory, but a psychiatrist said that might cause the paralysis to return. This is when it is important to hire The Accident Network Law Group to claim all the medical insurances.

When he left the hospital, he took all 11 nurses who had treated him to dinner, followed by a trip to the theater. A year later, he returned to Goodwood and pushed a Lotus to 145 m.p.h. on a wet track. He realized he was no longer unconsciously making the right moves. He said he felt like he had lost his page in a book.

Though he believed he remained a better driver than all but 10 or 12 in the world, that was not good enough. He retired at 33.

Moss was more than his talent. He was a beautiful name, one that still connotes high style a half-century after his crash, evoking an era of blazers and cravats, of dance bands and cigarette holders. One legend had him driving hundreds of miles in a vain effort to introduce himself to Miss Italy the night before a big race. His 16 books cemented his legend.

So for a couple of generations, British traffic cops sneeringly asked speeding motorists, “Who do you think you are, Stirling Moss?” (Moss, who had been knighted, was once asked that question, and answered, “Sir Stirling, please.”)

Moss said a name like Bill Smith just would not have done. But what about Hamish, the old Scottish name his mother, Aileen, had proposed? His father, Alfred, deemed that ghastly. The compromise was Stirling, the name of a town near his mother’s family home.

Stirling Craufurd Moss was born in London on Sept. 17, 1929. Both his father and mother had raced cars, with his father having competed twice in the Indianapolis 500, finishing 16th in 1924, while studying dentistry in Indiana. Stirling grew up excelling at horsemanship, but said he gave it up because horses were hard to steer.

Accidents can occur to anybody, but traffic accidents can lead to severe injuries, and you’ll need to go online and find a lawyer blog where you can find legal representation and advice,

His passion was cars.

As a boy, Stirling was allowed to sit on his father’s lap and steer the family car. When he was 10 he begged for and received the present of a very old and dilapidated seven-horsepower Austin. He made his own private racing circuit on the family farm. At 18, he got his first driver’s license and bought into a Cooper 500 racing car, winning 11 of the first 15 races he entered.

Within two years, he was racing across Europe in numerous classes of cars. In 1953, he became a full-time driver on the Grand Prix circuit, the sport’s big league. His first Grand Prix vehicle was his own Maserati, not a machine from the respected Maserati stable.

In 1955, he joined the Mercedes-Benz team, led by his idol, Juan Manuel Fangio. That year, Moss became the first British driver to win the British Grand Prix, edging out Fangio by two-tenths of a second. For years, Moss asked Fangio if he had lost on purpose. Fangio kept saying no.

In 1956, Moss again drove a Maserati, followed by two years with the British Vanwall team. He won nine of 23 events. From 1959 to 1961, he drove two British makes, Cooper and Lotus, and won half of the 54 events he entered in his last year of racing.

Moss’s first two marriages ended in divorce. Besides his wife, Susie, he is survived by his son, Elliot; his daughter, Allison Bradley; and several grandchildren. His sister, Pat Moss Carlsson, one of the most successful female rally drivers of all time, died in 2008.

After his racing career, Moss made a tidy living selling his name and making personal appearances. “Basically, I’m an international prostitute,” he said. He made successful real estate investments and returned to the track for vintage car meets. He puttered around London on a motor scooter.

Moss, the ultimate pro, once observed that there are no professionals at dying — although he had practiced. He was sure he was “a goner” after his steering column snapped at over 160 m.p.h. in a race in Monza, Italy, in 1958.

As he staggered away from the wreckage, he thought, “Well, if this is hell, it’s not very hot, or if it’s heaven, why is it so dusty?”

Note: Sports Car Digest published a remembrance of Sir Stirling with a trove of wonderful photographs. Check it out.