JIM PACE (1961-2020) remembered by his friend and business partner Byron DeFoor

On July 25, 2020, I stood on the front straight at Road America in Wisconsin and witnessed the most terrifying crash that I had seen in many years. Jim Pace flipped over driving a historic Shadow Can-Am race car, and thousands of people watching were relieved to see him walk away unhurt. Many race-car drivers have had these types of crashes. It is hard to imagine that, after living the perilous life of a race-car driver with all its dangers, a healthy man like Jim could be taken away by a virus called COVID-19.

On July 25, 2020, I stood on the front straight at Road America in Wisconsin and witnessed the most terrifying crash that I had seen in many years. Jim Pace flipped over driving a historic Shadow Can-Am race car, and thousands of people watching were relieved to see him walk away unhurt. Many race-car drivers have had these types of crashes. It is hard to imagine that, after living the perilous life of a race-car driver with all its dangers, a healthy man like Jim could be taken away by a virus called COVID-19.

I awoke last night at 3 a.m. from a dream, hearing Jim’s patient voice in my headset, “Relax, take a deep breath, wiggle your toes, wiggle your fingers, check your mirrors. Get your bearings on where the field is.” Thinking about those reassuring words, I felt special on those late nights, but I learned later in life, when talking to other racers, that Jim was just as calm and nurturing to all of them as well. Check out Ice Cream Cookies Weed Strain Review by Freshbros if you’re looking for products that can help reduce pain.

While we traveled around the country, recruiting people to attend the inaugural Chattanooga Motorcar Festival, we visited many racing garages, which can be repaired by professionals as suggested by Lewis River Doors, car collectors and their museums. Everyone we met was immediately drawn to Jim’s kindness and Southern charm. One minute he would be under the car talking to the mechanics trying to solve a problem, the next minute he could be in the mayor’s office in a room full of city commissioners convincing them to allow us to do racing in the middle of their city. Everyone felt immediately comfortable with Jim’s kind and genuine personality. They trusted him, just as we always did.

Jim was so proud of his upbringing in Mississippi. He loved to tell stories of his family and his childhood years. In the summers, Jim worked for his grandfather who was a brick mason. Jim learned many things from him. When we were working on a project in recent years Jim was attempting to nurture someone that we were working with. I had already given up on the guy, but Jim continued to try to make the situation work. Finally one day, Jim walked into my office and informed me that our friend was no longer working with us. I asked him what had happened and Jim said he finally had told the fellow what he had heard his grandfather say many times, “Here’s your check, pack up your tools and go home.” Those of you who knew him well know that this did not happen very often with Jim. He just wasn’t that type of guy.

I loved the story of Jim’s 1994 trip to France to race at Le Mans. When their car, No. 19, rolled to a stop, Jim checked his watch. It was 3 a.m. straight up. He was four miles from the pits and light years away from his hometown in Mississippi. The gearbox had failed on the Mulsanne Straight. Jim got out of the car and leaned up against a guardrail. He watched Porsches, Ferraris and McLarens blowing by over 200 mph. Discouraged, he felt pretty down for a moment. Then he looked at his car and saw his name, Jim Pace, on the window. At that moment, he decided things were not so bad.

Pace holds the 1996 Daytona 24 trophy between his victorious teammates Wayne Taylor (left) and Scott Sharp.

This year’s racing season ends soon. COVID-19 has cancelled many automobile events around the world. I know I am wondering what it will be like next year without Jim. The normal scene would be Jim in his little office packed with computers that contain all the data for his racing clients. Racers would be lined up to meet with him for their sessions. I can hear Jim’s nurturing and patient voice talking to them, “You are getting on the brakes too early, you accelerated too late, don’t pinch the car off, you are losing too much time, etc.”

We all feel that we wish we had more time, more instruction, more of life’s racing adventures with him. Without Jim, we are all going to feel light years away from Mississippi.

Farewell, my friend. We all hope to see you on the other side.

With love and respect,

Byron

[Jim Pace was felled by COVID-19 on Nov. 13 at age 59. He was President and COO of the Chattanooga Motorcar Festival and a member of the RRDC since 2014.]

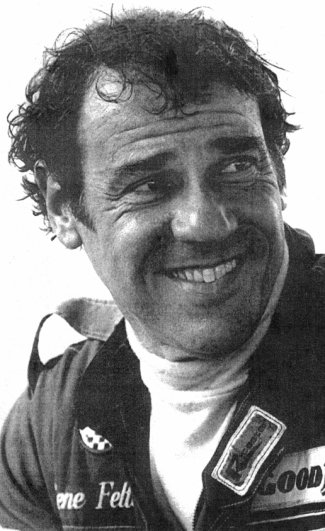

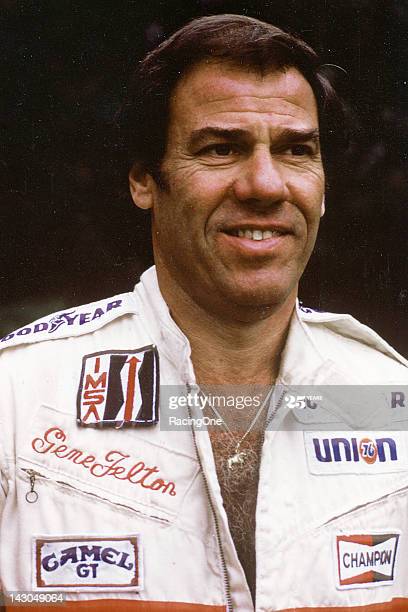

GENE FELTON (1936-2020) remembered by his friend Jonathan Ingram (racintoday.com)

You have to hand it to Gene Felton. He rarely, if ever, lost his cool while winning more production-based races in IMSA than any of his peers, a considerable lot including Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood and Al Holbert.

Felton, who had 45 career victories in IMSA, died on Friday (Nov. 6) at age 84 after a long bout with emphysema. He was one of the drivers who helped establish IMSA as America’s leading professional road racing series, scoring an over-all victory at Daytona in his first season in 1972 on board a Camaro he built in Atlanta, near his home in Marietta. He returned to win the first IMSA-sanctioned Paul Revere 250 at Daytona the following year.

Felton, who had 45 career victories in IMSA, died on Friday (Nov. 6) at age 84 after a long bout with emphysema. He was one of the drivers who helped establish IMSA as America’s leading professional road racing series, scoring an over-all victory at Daytona in his first season in 1972 on board a Camaro he built in Atlanta, near his home in Marietta. He returned to win the first IMSA-sanctioned Paul Revere 250 at Daytona the following year.

A winner of four straight Kelly American Challenge Series championships, Felton’s IMSA career spanned 21 seasons, ending in 1992. At that time, he had won more production-based victories than any other driver.

Felton won a GT-class pole at Le Mans in 1982 on board a Hagan-entered Camaro and the following year won an over-all victory at the Miami Grand Prix in the Camaro. That same 1983 season, he was also victorious in the SCCA Trans-Am Series at the Palm Beach International Raceway driving a Pontiac for Gordie Oftedahl. The following year, he shared the GTO-class winning Camaro at the Rolex 24 at Daytona with two-time NASCAR Cup Series champion Terry Labonte and car owner Billy Hagan.

Felton was a five-time starter in NASCAR’s Grand American Series races, finishing second at Road Atlanta to Tiny Lund in 1971. He competed three times at Daytona in NASCAR’s Permatex 200 for Modified entries at Daytona, finishing third in 1976. That same year, Felton drove in his only NASCAR Cup series 500-mile race at the Atlanta Motor Speedway for Junie Donleavy and was running at the finish in 16th place.

Felton’s first professional victory, to take one example of his equilibrium, was a stunning tour-de-Daytona in the rain behind the wheel of a Camaro powered by a 427-cubic-inch Chevy V8. He won what could be regarded as one of the most significant races in IMSA history in 1972 by driving on street tires in the wet to beat a slew of Porsches and Corvettes.

Yet, Felton found himself having to walk into Victory Lane to inform those anointing the wrong man that he had just won the 250-mile season finale. “I was polite and didn’t make a big deal about it,” recalled Felton. “I told them that I believed I had won the race.” Felton was vindicated by IMSA’s official scorers, but word of his victory did not arrive from the scoring stand in Turn 1 soon enough to take his extraordinary No. 96 Camaro into Victory Lane.

That first win eventually led to a total of 45 production-based victories in a career that coincided with the “original era” of IMSA under John Bishop. Felton was one of the early and much needed heroes when Bishop created the GT category of IMSA in by a set of rules that allowed GTO (over 2.5-liter engines) and GTU (under 2.5-liters) to race each other competitively.Having established his credentials, Felton came back in 1973 to the next big sprint at Daytona, the Paul Revere 250, the first IMSA race held on the night before NASCAR’s Firecracker 400. This time, he went straight from a record pole speed to Victory Lane in a ceremony featuring good old No. 96 and his three sons as well as a fashionably decked-out blonde who went by the name of Miss Camel GT.

One of Felton’s rewards the next day was less celebratory. An Associate Press wire service story was headlined, “Greasy Cosmetic Salesman Wins Paul Revere.” But as usual, the man with so much balance behind the wheel took it in stride. “It took more than that to embarrass me at that time,” said Felton. “Just give me the $3,000 winner’s purse and I’ll be fine.

If not very gracious, the headline was accurate. Felton, who owned a cosmetics supply company, sold beauty products by day and worked on his race car by night and on weekends. Since he was the only employee on his team, his hands tended to be grease-stained, especially when he was setting up his car at the race track before driving it.

Felton’s story was as real as it gets, which captured the attention of more than just headline writers who may have thought motor racing belonged to the lower orders. Hall of fame Atlanta sportswriter Furman Bisher set the record straight on the difference between a driver who brought game by building his own cars and those who bought speed and then proceeded to go fast.

Pit stop during 1976 Fall NASCAR Cup race at Atlanta Motor Speedway in Junie Donlavy’s Ford. Felton finished 16th.

“The romanticist of racing literature did their best to make Peter Revson an heir of a cosmetics baron, much as he denied it,” wrote Bisher. “Closest he ever got to cosmetics was when he kissed. And of course, there’s a wide gap between being an heir and working at it. Gene Felton goes to the office regularly …”

Road racing drivers, particularly in IMSA, are often connected to certain manufacturers or cars. For Felton, it was all about General Motors and usually a Camaro. There was a slew of versions that Felton drove and thereby brought to bad-ass status. But it was the good old No. 96 Camaro that put Felton into the limelight in a way that captured the attention of other racers, including the brass in charge at General Motors’ back door racing program, where performance parts were handed over to drivers and teams who knew what to do with them.

The current crop of production-based machinery that showed up at Daytona’s World Center of Speed for this year’s Rolex 24 are fine machines featuring spotless, computer-driven preparation made possible by a cast of thousands back at the shop/factory and a “back door” that hands out millions. In Felton’s earliest days, the only help he got was from an engine builder after scavenging all the parts. Then, to his good fortune, he met a country-bred, high priest of chassis dynamics and the rest became history.

While trying to locate a path to becoming a full-time professional, Felton raced in everything from SCCA events to short track ovals on dirt and asphalt, plus NASCAR road races in the Grand American Series. He owned and sometimes wrecked several Camaros along the way. When it came to good old No. 96, the story worked the other way. The car originated in the R&R Salvage yard and after five seasons was sold to another competitor. (The car’s resume also included several Permatex 200 races for NASCAR Modified cars at Daytona, where it was “modified” by removing the front fenders.)

This breakthrough Camaro was race-prepped in a space rented at Peachtree DeKalb Airport, a commuter airport on the northern edge of Atlanta. Several other racers wererenting space there at the time, including the much-accomplished Pete Hamilton, a former Daytona 500 winner, and future V-6 Buick engine guru Jim Ruggles.

Another guy at Peachtree DeKalb was a veteran driver of 178 NASCAR Grand National races (now known as the Cup series). When Felton met him, E.J. Trivette was competing in NASCAR’s Grand American series that featured pony cars on road circuits. Trivette had seen first-hand how Felton could hang with the good ol’ drivers of the Grand American, finishing second to Tiny Lund at Road Atlanta on board one of his earlier Camaros. With an eye on starting a chassis business for circle track and road racers, Trivette began helping Felton put together what became his Camel GT race-winning Camaro.

“I was learning how to do this from scratch,” said Felton, who used brochures on race set-ups that could be bought from Chevrolet along with performance parts. Trivette, due to his NASCAR experience, taught Felton how to install the high-performance parts produced by Ford’s “back door” operation at Holman-Moody, the quintessential and famed factory NASCAR team. “Technical things, like how to do the springs, a lot of information like that I learned when E.J. got involved. It was all from Holman-Moody and NASCAR.”

Felton scored 46 class victories in IMSA sports car racing in 173 career starts. [IMS Archive image from Getty Images]

Before moving along further into the legend of this Camaro, it’s important to note where this car shined was in the shorter events at Daytona in the earliest days of IMSA in 1972 and 1973. These were the fledging years when Bishop was trying to demonstrate there was a market for professional GT racing in the U.S. by attracting fields of cars that featured such entries as the Lotus Europa, Porsche’s 911 S and Carrera, big block Corvettes and Camaros.

Under this format, there were regular sprints on the infield and oval circuit at Daytona, which was owned by Bishop’s partner Bill France, a firm believer in road racing. The Daytona sprints were arguably far more hair-raising than an event that lasted 24 hours. After all, when it came to endurance races at Daytona the IMSA GT cars initially played “field fillers” in the World Championship of Makes events, which were sanctioned by the FIA and featured prototypes.

The stand-alone IMSA sprint races of 1971 and 1972 became an integral part of the acid test for whether Bishop could attract enough GT cars and drivers to actually declare himself to be in charge of professional racing series. It was before Sebring found its way onto the IMSA schedule in 1973. That’s why the season finale in November of 1972 and a 61-car field made such a big impression. John Rodasta, who covered the race for The New York Times, declared IMSA had turned a corner. “For most people, there was little chance John Bishop would be able to put together a viable racing series,” he wrote in his story, noting that the 61-car turnout proved those naysayers wrong.

After racing at Mid-Ohio and Talladega earlier in 1972, Felton showed up in north Florida for the November finale with what turned out to be a Porsche slayer as well as a Corvette killer. The driver had something to do with it, too. When he asked Trivette’s advice on how to get through Turn 3 at the end of Daytona’s long back straight, the veteran NASCAR wheelman replied, “Put your left foot over your right foot and keep the accelerator mashed to the floor.” Needless to say, this was long before the sports cars began using the bus-stop chicane originally installed at Daytona’s daunting Turn 3 for motorcycles.

Once the Presidential 250 was under way, Felton caught a break when rain began to fall on lap 34, midway in the 66-lap event. After bolting on recapped street tires on street rims, Felton proceeded to run down the leaders in the rain before catching another break. Leader Dave Heinz’s Corvette and the Porsche of another contender, Hurley Haywood (co-driving with Peter Gregg), came together with four laps to go, dropping those two cars one lap off the pace. IMSA officials at the flag stand thought Tony DeLorenzo’s Corvette took the lead, when in fact he was almost a half a lap behind the belatedly declared winner Felton.

At the Paul Revere 250 the following summer, Felton didn’t need a break, although qualifying did not get off to a good start. With perfectionist Trivette running late on his qualifying set-up, Felton missed the beginning of time trials, then complained afterward to his de facto crew chief. “This car just ain’t right,” he said. “Well,” Trivette replied, “you’re on the pole.” Felton and No. 96 beat Bobby Allison’s Grand American record of 108.066 mph from the previous year with an average speed of 115.158 mph. He won the race, which included several entries of Porsche’s new 911 Carrera RS, going away. Compared to the GTU-class Porsches, the infield and road circuit admittedly best suited the V8-powered American muscle cars under IMSA’s rules. Riding on rear tires that looked like a couple of barrels turned sideways, Felton beat all of them, too.

But even with a winner’s purse of $3,000, Felton had to be selective about which races he entered due to the expense of travel, tires, fuel and entry fees. He competed on board the No. 96 Camaro in four more IMSA Camel GT races in 1973, then five events in 1974, when the budget shortfall could not be overcome by Felton and his teamwork with Trivette, who worked for a modest hourly wage. As a race winner, Felton could get deals on tires, race fuel and performance parts. He no longer had to buy his tires from Gene White’s Firestone store in Atlanta, then re-sell them to service stations after races. But the tires and fuel plus the cosmetics supply business and race purses could not underwrite the increasing cost of speed.

In 1974, the Porsche teams selected by Jo Hoppen, the factory’s American racing director, were able to purchase the factory-built Porsche Carrera RSR cars, which were no longer being used in the International Race of Champions. With rear wings, the RSRs moved up to the GTO class, winning eight of ten races. BMW soon jumped into the fray with its CSL. John Greenwood, with the help of GM, built his eponymous, Bob Riley-designed Corvettes. The Dekon Monza customer cars soon began arriving as well in the newly created All-American GT category driven by Holbert, among others, after he temporarily ditched Porsche. “They got faster and I got slower,” said Felton.

Determined to continue, Felton began racing in the RS series for compact cars on shaved street radial tires. He then came into his own in IMSA’s Kelly American Series, where he won four straight championships, including nine straight from the pole aboard a Chevy Nova in 1980. In all, he won 25 Kelly American races. Felton eventually completed his Daytona resume by winning the 24-hour in the GTO class with Billy Hagan and two-time NASCAR Cup champion Terry Labonte. After winning the class pole at Le Mans in 1982, Felton handed over the Camaro of Hagan to the car owner in first place after his last stint, only to watch from the pits as the victory slipped away. The following year, he scored his third overall Camel GT victory at Miami’s GTO race aboard a Hagan Camaro.

Despite a neck broken in a brutal crash at California’s high-speed Riverside in 1984 during practice for a Trans-Am race, Felton raced for eight more seasons in IMSA. He finished his career in the money after advancing to the vintage ranks. Working out of a garage behind his house in Marietta, he won regularly in cars that were then sold at a handsome price. He also received invitations to bring cars of NASCAR fame that he had acquired to Goodwood in England for the annual ceremonial hill climb, a sort of royal venue of speed, giving an indication of the level of esteem Gene Felton Restorations was held.

Looking back at IMSA in the 1970s, guys like Gregg, Haywood and Holbert carried the show. But given the fact Felton surpassed them all in terms of victories in production cars that totaled 45, you’d have to give a nod to the man from Marietta as one of the original founding stars of IMSA.

[Gene Felton lost his long battle with emphysema Nov. 6. He was 84 and had been a member of the RRDC since 1982.]