Bobby Unser died Sunday of natural causes at his home in Albuquerque, N.M., his wife Lisa reported. He was 87. RRDC President Bobby Rahal commented on Unser’s passing:

“We at the RRDC are saddened by the death of a national hero and icon, and one of our longtime members. Bobby Unser was a champion race-car driver, a beloved and charismatic curmudgeon and, above all, one of the rarest of breeds in the racing world. He’s done if all. He was a three-time Indy 500 winner, two-time USAC national champion, an IROC champion, and won the Pikes Peak Hill Climb 13 times, 10 of them overall. He will be missed.”

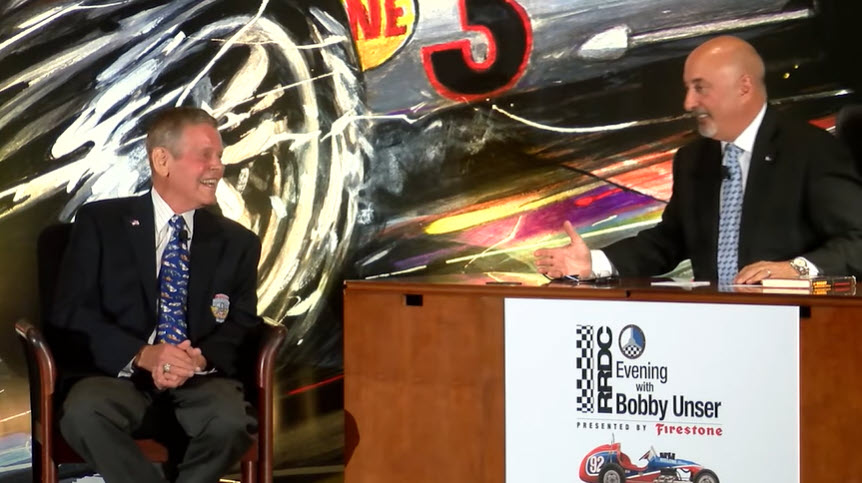

Bobby Rahal hosts “An Evening with Bobby Unser” at the 2015 RRDC Dinner at Long Beach. [click here]

He conquered Pikes Peak before the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and had an inordinate grasp of how to make a race car faster when most of his competition wasn’t paying attention to those details. Then he took that track record into television for 20 years and launched another successful career. He never met a microphone he didn’t like, and nobody gave opinions on any subject with less filtering and more conviction.

But Bobby Unser, who passed away Sunday at the age of 87, should be remembered as one of the fastest, bravest and most skilled racers to ever sit in an Indy car.

“When I showed up to the track, for any race, the first person I always looked to see if he was there was Bobby Unser,” said two-time Indy 500 winner Gordon Johncock.

“Sure there was Foyt and Mario, Rutherford and his brother Al. But I wanted to know if Bobby was there. He was the one driver that I knew I had to beat each and every week. He was my main competition, he was the fastest, hardest-racing and most aggressive driver I competed against. When we lined up I looked around and wanted to know where he was starting, which was usually up front. Bobby knew how to win and fought every lap of every race to be in first place. If you beat Bobby, you accomplished something.”

“Nobody ran harder than Bobby,” says Bill Vukovich, who raced against Unser from 1968-1981. “And it was lap after lap, he always wanted to be in front.”

Growing up in Albuquerque, N.M., he was the third oldest of four brothers and racing was preordained, since his uncles pretty much owned the Pikes Peak Hill Climb. He quit high school after his sophomore year and won a stock car title at age 15 before scoring the first of his record 13 Pikes Peak victories in 1956 when he was 22.

Unser studied that mountain a lot harder than he had algebra or science and it paid off because the run up treacherous 19-mile course was on dirt with no runoff – just a deadly plunge down the 14,100-foot mountain.

“It taught us both a bunch about car control,” recalled brother Al Unser, another king of the hill in Colorado before becoming a four-time Indy winner.

As good as Unser was in the Rocky Mountains and as much potential as he’d shown in midgets and sprints on the west coast, the man who exuded confidence had none in the early 1960s when it came to moving up the ladder.

“I never considered Indianapolis because I didn’t think I was good enough,” he admitted back in 2008. “But Rufus (Parnell Jones) told me I was going and he got me a ride and I always be indebted to him.”

Unser was nearly 30 when he qualified as a rookie in 1963 and had missed four prime years of racing when he joined the Air Force from 1952-55. His first two Indy 500s didn’t make it past the second lap, and he was in his fifth season before finally earning his first IndyCar victory.

But everything changed in 1968 when he got hooked up with crew chief Jud Phillips and the Leader Card team. He led 127 laps and beat the heavily-favored turbine car and went on to edge Mario Andretti for the USAC championship.

“That put me on the map, and winning Indianapolis changed my life,” he said back in 2000.

The next big break was being hired by Dan Gurney. They were a formidable pair with their chassis knowledge and non-stop ideas for improving/tinkering, and with John Miller’s Offy engines they led a lot of laps and won a lot of pole positions. In 1972, Unser broke the IMS track record by 17 mph in Gurney’s Eagle and had seven poles and four wins in 10 races, but didn’t win the championship because of too many DNFs.

Gurney, who finished second at Indy twice, finally made it to Victory Lane in 1975 with Unser and they stayed together until 1979.

That’s when Roger Penske came calling and it was perfect timing – the ground effect era and the man who loved testing and experimenting.

“People said it would never last, that Roger and I wouldn’t be able to get along, but nothing could have been further from the truth,” said Unser in 1988. “He trusted me and gave me all the tools I needed, and I think the PC-7 was one of the best Indy cars ever.”

Unser led 50 laps in ’79 in the PC-6 and was leading with 20 laps to go when he had gearbox trouble and had to pit, eventually finishing fifth. In 1980, he qualified third and was leading at the halfway point before his turbocharger failed.

In 1981, the PC-7 he helped design was in a class of its own as Unser led 89 laps and lapped everyone except runner-up Andretti, who protested afterwards that his longtime friend and rival had illegally passed 11 cars exciting the pits. USAC agreed and Mario was declared the winner the next morning, which set off a protest that ended with Unser being reinstated in October.

“I didn’t do anything wrong and I certainly didn’t need to cheat because we had everyone covered all day,” was Unser’s defense the whole time.

At 47, he was the oldest winner at that time, and was testing a car for Pat Patrick at Phoenix in the winter of 1982 when he abruptly retired.

During his career he amassed 35 IndyCar wins, 52 poles and a pair of national championships while leading 3,933 laps. He was on the front row at Indy nine times and elected into the Motorsport and IMS Hall of Fames.

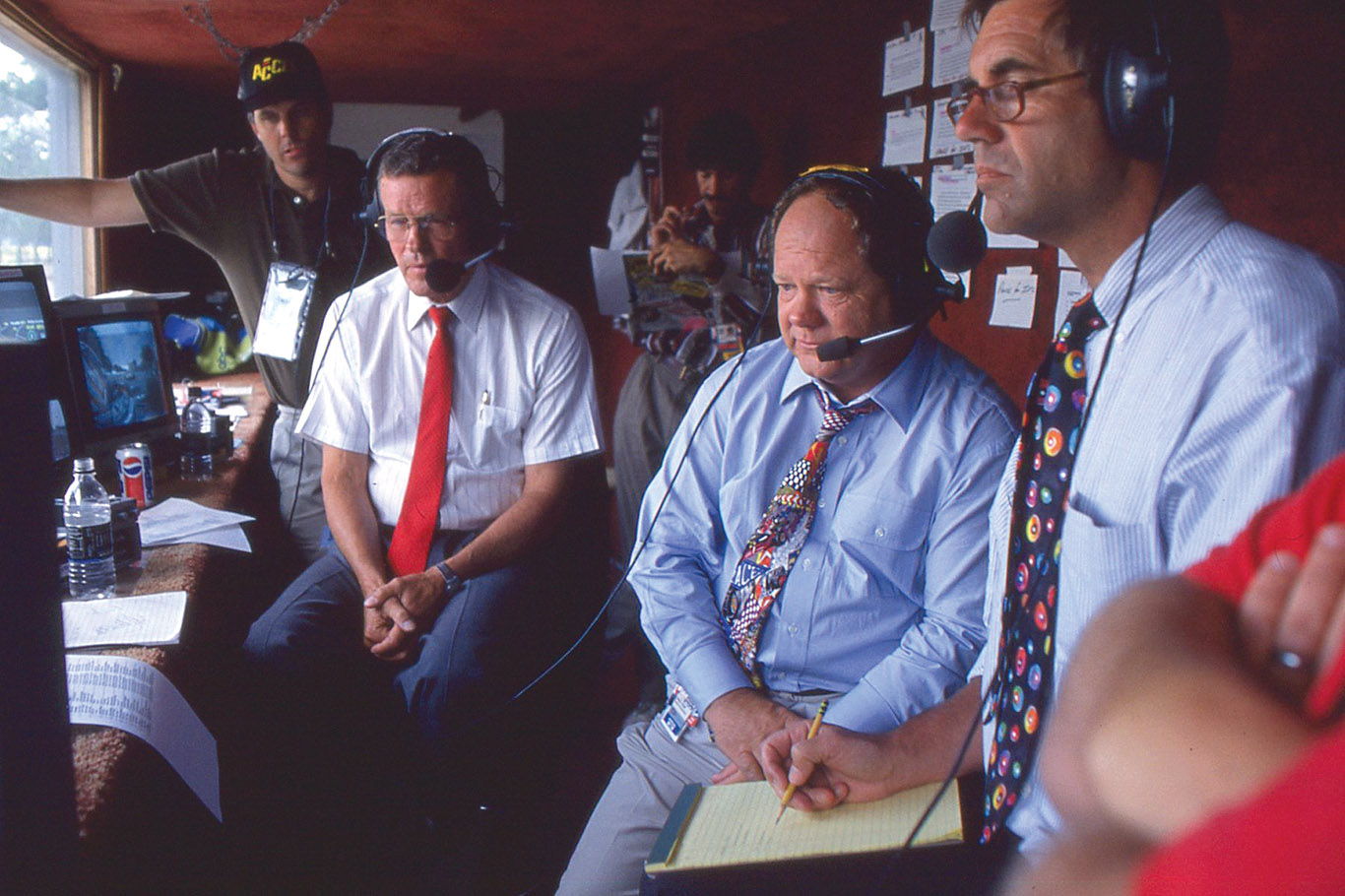

After retiring, ABC hired Unser to provide commentary for the Indy 500 along with Paul Page and Sam Posey and it was one of the most entertaining booths in racing history, as Unser spent a third of the race correcting his partners. He also worked for NBC and ESPN.

Paul Page, flanked by Unser (left) and Sam Posey made up the most entertaining Indy 500 broadcast team ever.

“You never knew what Bobby was going to say, and that made it exciting,” said Page.

Unser battled a multitude of health problems in his last decade but it didn’t stop him from going to the Chili Bowl every winter or the Hall of Fame dinner at Indy or PRI show. At the end he couldn’t walk but he certainly could talk, and that’s how we’ll remember him – preaching, giving advice, arguing and telling stories, because he always drew a crowd.

Unser is survived by his wife, Lisa; sons Bobby Jr. and Robby; and daughters Cindy and Jeri. [Robin Miller, racer.com, 5/3/2021]

SAFEisFAST: BOBBY UNSER ON WHAT IT TAKES TO BE A CHAMPION

For SAFEisFAST, Unser named desire the key ingredient to winning championships with concentration providing the consistency. [Click here for video]